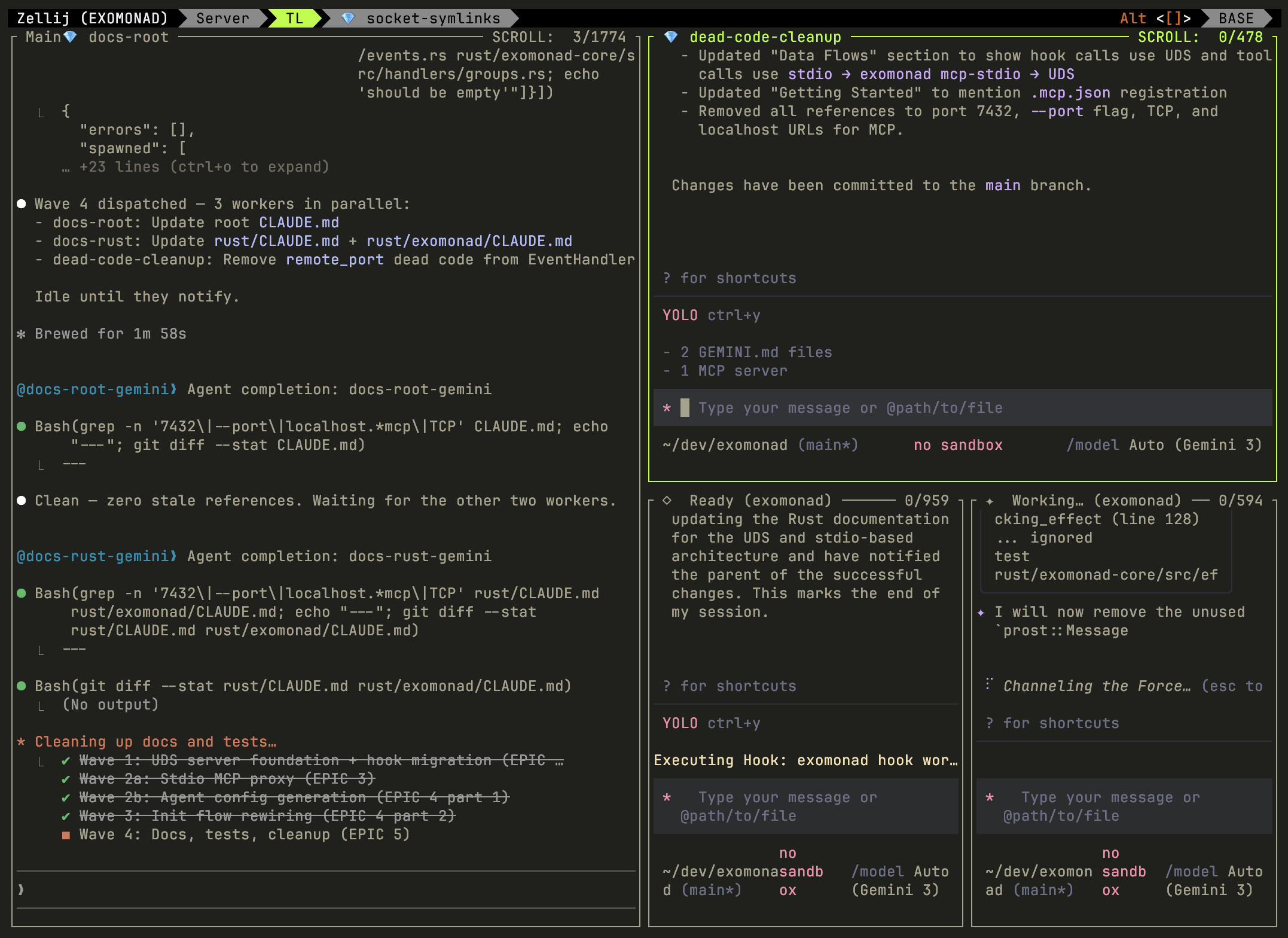

ExoMonad builds on Gastown’s worktree model, replacing “swarm of agents ramming PRs into main” with a tree of worktrees. It hooks into Claude Agent Teams’ messaging bus, so agents running other model architectures show up as native team members. It integrates with Copilot for GitHub PR reviews. It stitches together Claude, Gemini, Kimi, Letta Code, Copilot — using their existing binaries and your existing subscription plan.

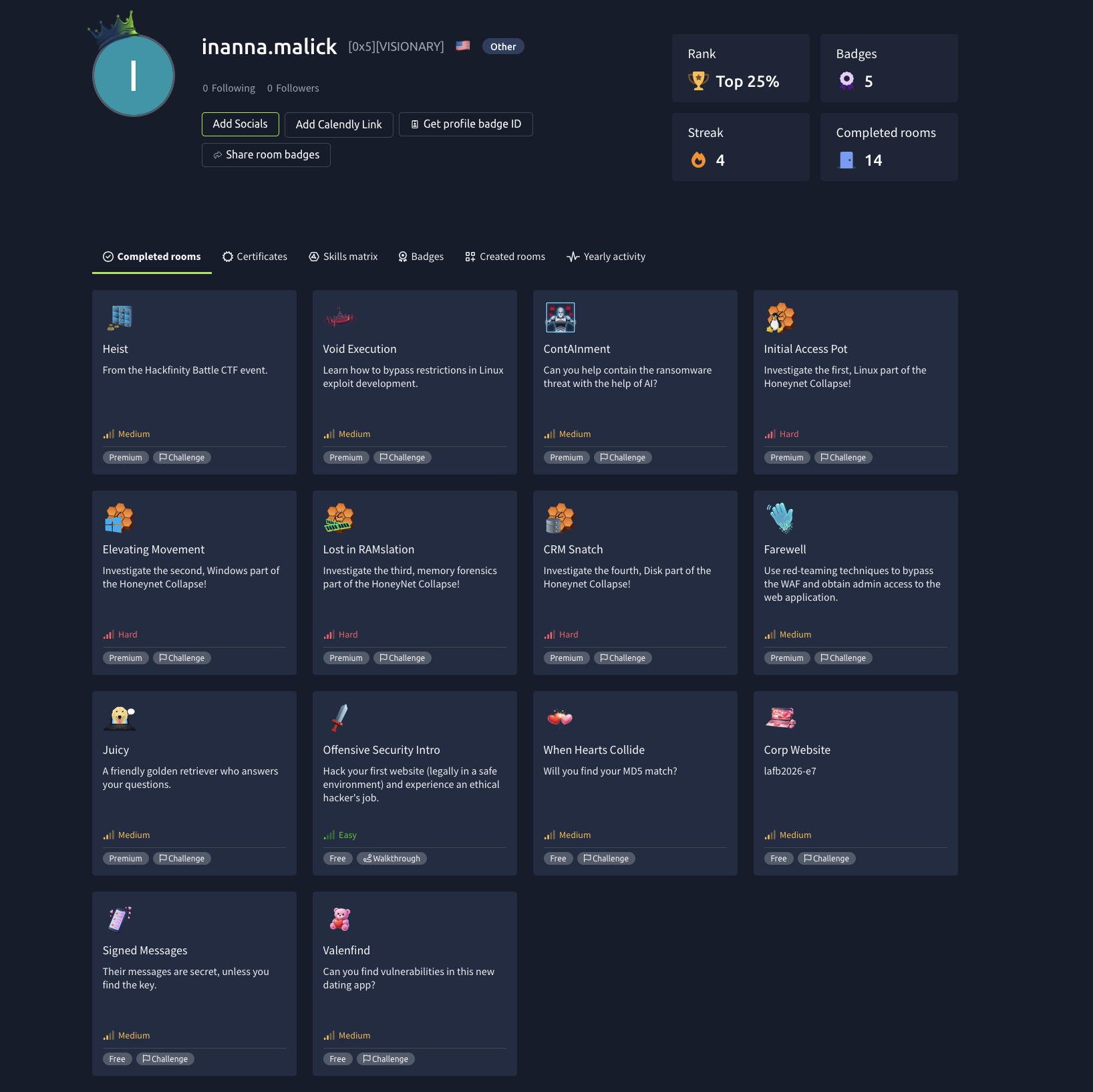

ExoMonad is radically reconfigurable. It ships with a default devswarm configuration that handles worktrees, coordination, iterating on pull requests, but when I needed a red team test harness, I just wrote another exomonad config and threw one together overnight 1.

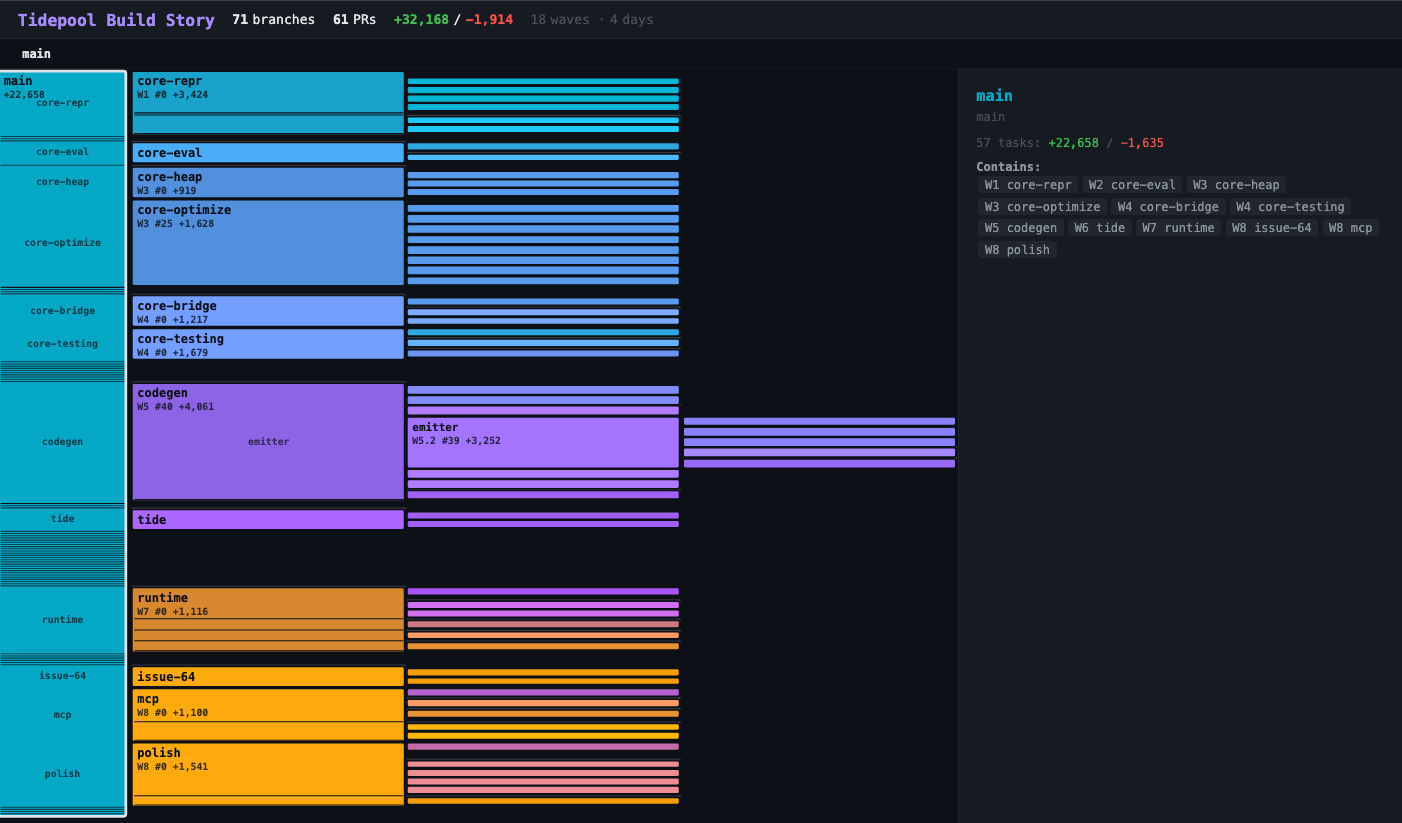

I started by using ExoMonad to build itself over 700 PRs. A few weeks ago, it felt ready to test out on other projects, so I used it to implement a new Haskell compiler backend using Rust.

[Read More]